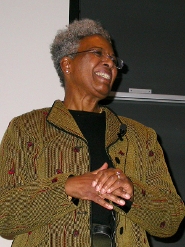

Dr. Nell Irvin Painter presented a talk titled, "Creating Black Americans: African American History and its Meanings, 1619 to the Present," based on her recently published book of the same name, on March 2 as part of the History Department Speaker Series. In her lecture, Dr. Painter discussed the writing of history and the ways in which that writing intersects with visual images.

Dr. Painter stressed the broad nature of history, pointing out that African American history is part of American history, and that American history in turn is part of world history. In order to explore the "Creation of Black Americans" as a part of this history, then, she explained first the approach to writing history in words, and contrasted this method with the construction of history through visual images.

With respect to the written aspect of African American history, Dr. Painter indicated the necessity to strike a balance between trauma and agency. In the past, she noted, histories of African Americans were generally comprised of stories of bad things that white people did to black people; these histories focused on the ways in which slavery cost black people, both psychologically and materially. Later, the writing of history shifted to reveal instead a story of African American agency; it portrayed black people as the makers of history. Today, according to Dr. Painter, written history often combines these two extremes. It focuses on African American agency while at the same time taking note of limitations that inhibited and continue to inhibit that agency.

Writing, though, is not the only approach to history, as Dr. Painter illustrated. Visual images reveal elements of history that writing is unable to capture and succinctly show the balance between agency and trauma. African American artists, Dr. Painter noted, often explain their art as expressive of their desire to show the unknown history and the unknown beauty of their people. Dr. Painter showed first "The Janitor Who Paints," a painting completed in 1937 by Palmer Hayden. The work features an African American janitor/painter painting an African American mother and child. The painting, according to Dr. Painter, reveals both trauma and agency; it is perhaps depressing in that the painter must rely on work as a janitor, but it is simultaneously hopeful as it puts him in the position of Creator.

Reinforcing the nature of visual constructions of history, Dr. Painter also showed images of two 20th century sculptures of Sojourner Truth. Inge Hardison, in her 1968 "Sojourner Truth," and Barbara Chase-Riboud, in her 1999 "Sojourner Truth Monument," both "do things in these figures that we historians simply cannot do," as Dr. Painter noted. She stressed the "heartfelt meaning that artists can put into history." Artists, Dr. Painter said, are able not only to show the trauma and agency of history, but also to show how that history is relevant to and influences the present.

Dr. Painter highlighted three specific kinds of images, though, that have not attracted black artists: those that depict the Atlantic slave trade, the American Civil War, and Reconstruction. She showed examples of the few existing images that fall under these categories, and noted how they simultaneously show "what our history might have been and also what it is and might be in the future." She cited, for instance, "The New Order," a 1998 painting by John Jones that depicts General Robert E. Lee atop a black horse, next to Colin Powell on a white horse.

Noting that "we make a history depending on what we need to know now," Dr. Painter indicated that these visual images, together with written history, combine to help structure an African American identity.

Dr. Painter was introduced by President Stewart and Assistant Professor of History Chad Williams, who noted that Dr. Painter's name "is synonymous with Africana Studies." Until her recent retirement, Dr. Painter was the Edwards Professor of American History at Princeton University. Her talk was sponsored by the Africana Studies Department and the Office of the Dean of the Faculty.

-- by Sarah Lozo '06

Dr. Painter stressed the broad nature of history, pointing out that African American history is part of American history, and that American history in turn is part of world history. In order to explore the "Creation of Black Americans" as a part of this history, then, she explained first the approach to writing history in words, and contrasted this method with the construction of history through visual images.

With respect to the written aspect of African American history, Dr. Painter indicated the necessity to strike a balance between trauma and agency. In the past, she noted, histories of African Americans were generally comprised of stories of bad things that white people did to black people; these histories focused on the ways in which slavery cost black people, both psychologically and materially. Later, the writing of history shifted to reveal instead a story of African American agency; it portrayed black people as the makers of history. Today, according to Dr. Painter, written history often combines these two extremes. It focuses on African American agency while at the same time taking note of limitations that inhibited and continue to inhibit that agency.

Writing, though, is not the only approach to history, as Dr. Painter illustrated. Visual images reveal elements of history that writing is unable to capture and succinctly show the balance between agency and trauma. African American artists, Dr. Painter noted, often explain their art as expressive of their desire to show the unknown history and the unknown beauty of their people. Dr. Painter showed first "The Janitor Who Paints," a painting completed in 1937 by Palmer Hayden. The work features an African American janitor/painter painting an African American mother and child. The painting, according to Dr. Painter, reveals both trauma and agency; it is perhaps depressing in that the painter must rely on work as a janitor, but it is simultaneously hopeful as it puts him in the position of Creator.

Reinforcing the nature of visual constructions of history, Dr. Painter also showed images of two 20th century sculptures of Sojourner Truth. Inge Hardison, in her 1968 "Sojourner Truth," and Barbara Chase-Riboud, in her 1999 "Sojourner Truth Monument," both "do things in these figures that we historians simply cannot do," as Dr. Painter noted. She stressed the "heartfelt meaning that artists can put into history." Artists, Dr. Painter said, are able not only to show the trauma and agency of history, but also to show how that history is relevant to and influences the present.

Dr. Painter highlighted three specific kinds of images, though, that have not attracted black artists: those that depict the Atlantic slave trade, the American Civil War, and Reconstruction. She showed examples of the few existing images that fall under these categories, and noted how they simultaneously show "what our history might have been and also what it is and might be in the future." She cited, for instance, "The New Order," a 1998 painting by John Jones that depicts General Robert E. Lee atop a black horse, next to Colin Powell on a white horse.

Noting that "we make a history depending on what we need to know now," Dr. Painter indicated that these visual images, together with written history, combine to help structure an African American identity.

Dr. Painter was introduced by President Stewart and Assistant Professor of History Chad Williams, who noted that Dr. Painter's name "is synonymous with Africana Studies." Until her recent retirement, Dr. Painter was the Edwards Professor of American History at Princeton University. Her talk was sponsored by the Africana Studies Department and the Office of the Dean of the Faculty.

-- by Sarah Lozo '06