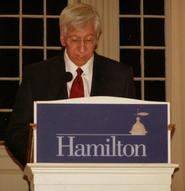

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) President Myles Brand spoke to a packed Hamilton College Chapel on Tuesday, Oct. 2, about the alignment of intercollegiate athletics and higher education. Brand made a case for the continued link of the two institutions, stating that athletics is "connected to higher education because, and only because, it helps educate."

Brand's experience with intercollegiate athletics comes from an administrative and academic perspective. After serving as president of the University of Oregon and the University of Indiana, he assumed the presidency of the NCAA in 2003. He also holds a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Rochester, with a research focus on human intentions and action that informed his remarks.

The lecture began with an illustration of the historical context of collegiate sports. Brand described how the first college athletics in the 19th century were student-run and originated as a diversion, not part of academic programs. Nevertheless college sports in the United States developed into interschool rivalries and traditions (unlike Europe, where athletics held to the within-school club sports model). College athletics were only placed under control of college administrations in response to President Theodore Roosevelt's concern about the high number of fatalities from college football (in which 19 players died in 1905 alone). In future years, faculty came to take a greater role in sports so that by the end of World War II intercollegiate athletics were mainly administered by professionals. Since then, radio and television expanded the appeal of college sports to large audiences, but created controversy because of their intense popularity that some feared would compromise academic institutions.

Much of Brand's talk was a response to criticisms that athletics are extraneous to a college system or that athletics even "debase" academics. Brand pointed to the values of athletic participation by comparing student athletes to students with other unique talents, such as musicians. In Brand's view, both these types of students enter college with developed skills, an ambition to succeed professionally and a commitment to spend time reaching their goals in the field. Through these extracurricular pursuits, students develop important skills; in the case of athletics, these skills include teamwork, self-discipline, persistence and ability to lead. Brand suggested that there is "no better way than through athletic participation" to learn these skills that turn students into "citizens of the world."

He then rebutted some specific criticisms of intercollegiate athletics. The first was that college sports lose their value when they expand to a large size. Brand answered that we do not make this same argument to imply that large universities "distort the value of higher education" as compared to smaller schools, and as such scale should not be an issue.

Another criticism of sports attacks the consumption of school resources by athletics budgets. While Brand recognized this can be a problem, he suggested it is not necessarily of concern, considering that university budgets at large have increased in size. He pointed to the budget of Ohio State University, in which the seemingly large sports program receives $10 million but is dwarfed by the billions of dollars spent in the school's overall budget. Thus, Brand concluded that "the size of the budget itself does not abuse the purpose of higher education."

He then addressed the argument that attention paid to athletics diverts from the goals of higher education, which he opposed on the basis that "all activities have educational value." Brand later pointed to the concrete evidence of the federal government's Title IX statute, which provides equal athletic opportunities between genders based on the explicit legal assumption that athletics are part of education.

Brand also argued that simply because athletics make money they should not be considered non-academic; if lectures could also be televised for revenue, it should be acceptable to do so. He noted that the Ivy League colleges (a grouping actually based on athletic status) have not suffered poor academic reputations from their associations with athletics.

Next Brand turned to the question of how to better integrate athletics into higher education, given that he had shown the two institutions are aligned. First, he argued that intercollegiate sports must be "integrated into the administrative structure" of institutions. While some college athletics programs have become distanced from their college -- in order to increase revenue through private sources and because of hostility at their physical nature -- Brand insisted that athletics administrators must remain college staff. He also said that sports must share the values of their university, including a focus on "excellence" over winning. Indeed, a focus on "winning at any and all costs" teaches the "wrong lesson" to student athletes, Brand said.

Brand also argued that student-athletes must remain regular students "as much as possible." Students with athletic abilities should be given the same treatment as students accepted for other special talents, such as music or art, and not receive special privileges for athletics alone. This vision is promoted by the new NCAA standards for athletics eligibility based on high school performance. However, Brand also reemphasized the power of athletics to enhance students' time-management and problem solving skills independently of coursework.

He then spoke of his goal of ensuring student-athletes achieve graduation rates equal to or better than the rest of the student body, partly by sanctioning coaches who fail to encourage academic performance. Brand pointed out that only football, men's basketball and baseball players have lower graduation rates than the national average; other Division I male athletes graduate about 70 percent of the time, on par with non-athletes. Thus, he seeks to address these poor-performing sports specifically, such as by correcting the perception of many men's basketball players that college is a lower priority than a professional career (when in reality only 0.01 percent of high school basketball players reach the NBA), and by preventing baseball players from losing ground when they transfer between schools.

Brand noted that graduation rate issues in sports are not evenly distributed among demographics; female athletes graduate at a high 87 percent rate, and African-American athletes graduate 11 percent more often than African-American non-athletes. In Division I schools only white male student athletes graduate at a lower rate than students in general (2 percent less), which Brand was unable to explain.

Brand concluded that athletics have enormous potential when they are integrated with the student body and the "high purpose" of college education. Ultimately, Brand's sentiments are expressed in a statement he quoted from Indianapolis Colts quarterback Peyton Manning; Manning said his college experience could not have been "as joyous, as rich" without athletics.

-- by Kye Lippold '10

Brand's experience with intercollegiate athletics comes from an administrative and academic perspective. After serving as president of the University of Oregon and the University of Indiana, he assumed the presidency of the NCAA in 2003. He also holds a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Rochester, with a research focus on human intentions and action that informed his remarks.

The lecture began with an illustration of the historical context of collegiate sports. Brand described how the first college athletics in the 19th century were student-run and originated as a diversion, not part of academic programs. Nevertheless college sports in the United States developed into interschool rivalries and traditions (unlike Europe, where athletics held to the within-school club sports model). College athletics were only placed under control of college administrations in response to President Theodore Roosevelt's concern about the high number of fatalities from college football (in which 19 players died in 1905 alone). In future years, faculty came to take a greater role in sports so that by the end of World War II intercollegiate athletics were mainly administered by professionals. Since then, radio and television expanded the appeal of college sports to large audiences, but created controversy because of their intense popularity that some feared would compromise academic institutions.

Much of Brand's talk was a response to criticisms that athletics are extraneous to a college system or that athletics even "debase" academics. Brand pointed to the values of athletic participation by comparing student athletes to students with other unique talents, such as musicians. In Brand's view, both these types of students enter college with developed skills, an ambition to succeed professionally and a commitment to spend time reaching their goals in the field. Through these extracurricular pursuits, students develop important skills; in the case of athletics, these skills include teamwork, self-discipline, persistence and ability to lead. Brand suggested that there is "no better way than through athletic participation" to learn these skills that turn students into "citizens of the world."

He then rebutted some specific criticisms of intercollegiate athletics. The first was that college sports lose their value when they expand to a large size. Brand answered that we do not make this same argument to imply that large universities "distort the value of higher education" as compared to smaller schools, and as such scale should not be an issue.

Another criticism of sports attacks the consumption of school resources by athletics budgets. While Brand recognized this can be a problem, he suggested it is not necessarily of concern, considering that university budgets at large have increased in size. He pointed to the budget of Ohio State University, in which the seemingly large sports program receives $10 million but is dwarfed by the billions of dollars spent in the school's overall budget. Thus, Brand concluded that "the size of the budget itself does not abuse the purpose of higher education."

He then addressed the argument that attention paid to athletics diverts from the goals of higher education, which he opposed on the basis that "all activities have educational value." Brand later pointed to the concrete evidence of the federal government's Title IX statute, which provides equal athletic opportunities between genders based on the explicit legal assumption that athletics are part of education.

Brand also argued that simply because athletics make money they should not be considered non-academic; if lectures could also be televised for revenue, it should be acceptable to do so. He noted that the Ivy League colleges (a grouping actually based on athletic status) have not suffered poor academic reputations from their associations with athletics.

Next Brand turned to the question of how to better integrate athletics into higher education, given that he had shown the two institutions are aligned. First, he argued that intercollegiate sports must be "integrated into the administrative structure" of institutions. While some college athletics programs have become distanced from their college -- in order to increase revenue through private sources and because of hostility at their physical nature -- Brand insisted that athletics administrators must remain college staff. He also said that sports must share the values of their university, including a focus on "excellence" over winning. Indeed, a focus on "winning at any and all costs" teaches the "wrong lesson" to student athletes, Brand said.

Brand also argued that student-athletes must remain regular students "as much as possible." Students with athletic abilities should be given the same treatment as students accepted for other special talents, such as music or art, and not receive special privileges for athletics alone. This vision is promoted by the new NCAA standards for athletics eligibility based on high school performance. However, Brand also reemphasized the power of athletics to enhance students' time-management and problem solving skills independently of coursework.

He then spoke of his goal of ensuring student-athletes achieve graduation rates equal to or better than the rest of the student body, partly by sanctioning coaches who fail to encourage academic performance. Brand pointed out that only football, men's basketball and baseball players have lower graduation rates than the national average; other Division I male athletes graduate about 70 percent of the time, on par with non-athletes. Thus, he seeks to address these poor-performing sports specifically, such as by correcting the perception of many men's basketball players that college is a lower priority than a professional career (when in reality only 0.01 percent of high school basketball players reach the NBA), and by preventing baseball players from losing ground when they transfer between schools.

Brand noted that graduation rate issues in sports are not evenly distributed among demographics; female athletes graduate at a high 87 percent rate, and African-American athletes graduate 11 percent more often than African-American non-athletes. In Division I schools only white male student athletes graduate at a lower rate than students in general (2 percent less), which Brand was unable to explain.

Brand concluded that athletics have enormous potential when they are integrated with the student body and the "high purpose" of college education. Ultimately, Brand's sentiments are expressed in a statement he quoted from Indianapolis Colts quarterback Peyton Manning; Manning said his college experience could not have been "as joyous, as rich" without athletics.

-- by Kye Lippold '10

Posted October 5, 2007