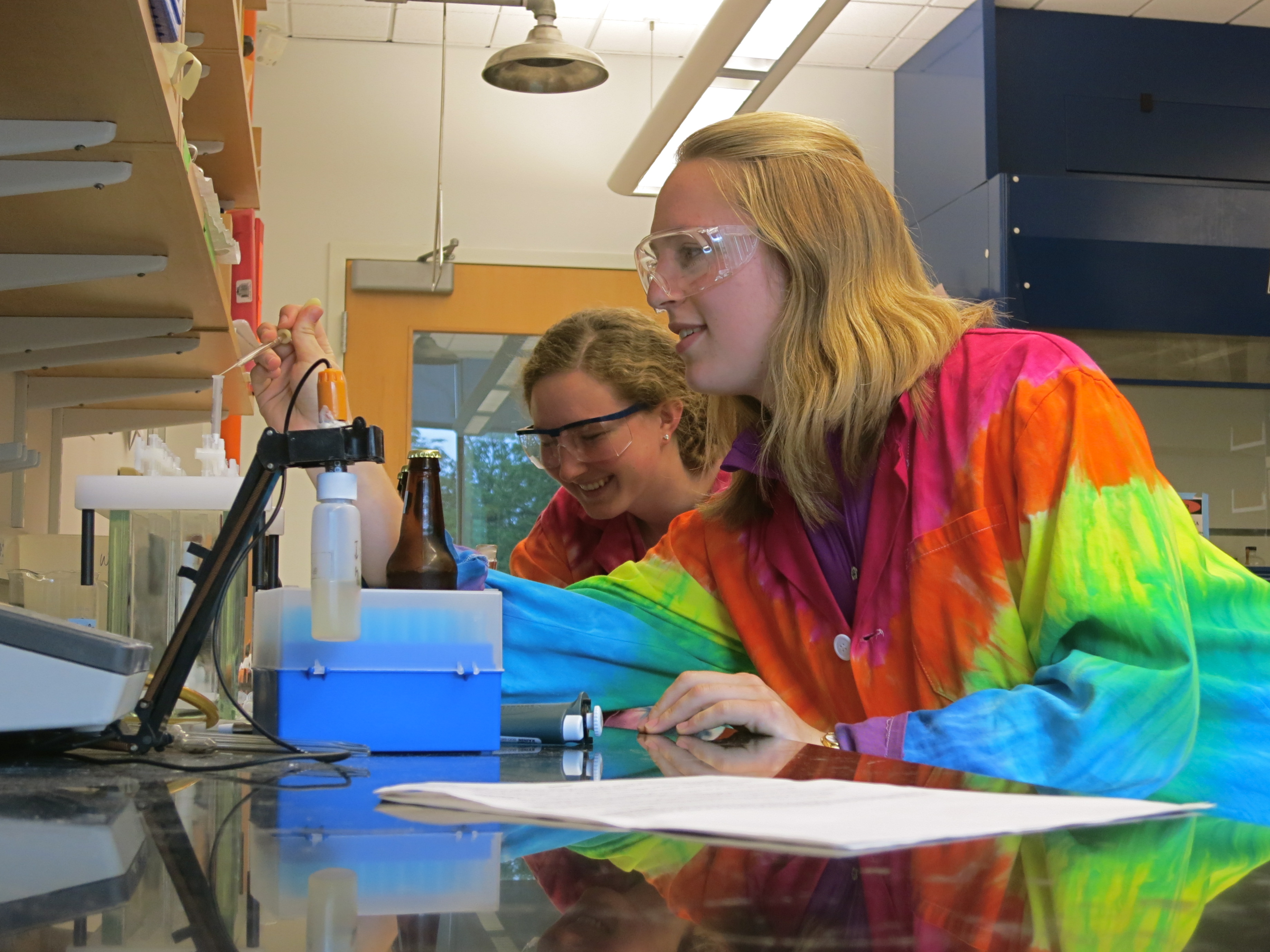

Because Bisphenol A, or BPA, has been identified as a factor in conditions including obesity, ADHD, reproductive complications and behavioral abnormalities, consumers and health officials have been alarmed at the presence of the chemical in food and drink products for years. In a summer research project, Lisbeth DaBramo ’15 and Rachel Sobel ’15 are measuring BPA levels in bottles and cans to identify how this toxic compound is introduced into our systems.

The United States produced 2.4 billion pounds of this artificial material in 2007, yet it has been banned in multiple countries, including Canada and Turkey. Sobel said “BPA became a household name when polycarbonate water bottles were introduced,” but the team is focusing on its presence in epoxy resins in food product containers.

Epoxy resins release BPA into the foods we ingest, which then allows the compound to enter our bodies. The caps are lined with the resins, and heat during the pasteurization process allows BPA from the resin to leach into liquid. The compound is more soluble in alcohol, so the team hypothesizes that beer will have higher concentrations of BPA than sodas.

Professor of Chemistry Tim Elgren is advising the team this summer. When speaking about their research, DaBramo “…finds it so applicable to everyday life…it affects everyone.” With the presence of resins in baby bottles, water bottles or beer bottles, most people have been exposed to BPA and may therefore experience its effects.

BPA is considered an endocrine disruptor because it mimics estrogen, a natural hormone. Many researchers are looking at BPA’s effects on our bodies, but the Hamilton researchers are exclusively focused on quantifying its concentrations in bottled and canned liquids.

Gas chromatography- mass spectrometry is one method used by the team. A gas chromatograph molecularly separates a sample, and then sends the product to a mass spectrometer. The “mass-spec,” then breaks each molecule into ionized fragments and measures their mass and charge. The team first performed trials involving solutions with known concentrations of BPA. This yielded their own internal standard curve, which will help determine the BPA levels in their blind experiments.

DaBramo noted that BPA was found to be an endocrine disruptor decades ago. Companies are now attempting to produce new varieties of the BPA-free plastic to avoid the known health problems.

Sobel believes her engagement in this project is influencing her to consider a career in public health and chemistry, both of which are integral to this research. DaBramo is uncertain about a career, but would like to continue working with analytical chemistry.

The team simply wants to bring awareness to how much BPA people are consuming and contribute to a larger scientific library on the topic. This work could then be applied to developing new, acceptable BPA levels in food product containers.

DaBramo is a graduate of Geneseo High School (N.Y.). Sobel is a graduate of Grafton High School (Wis.).