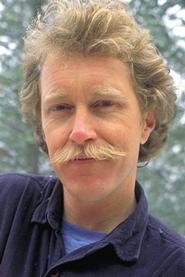

Broughton Coburn, author of The Vast Unknown: America’s First Ascent of Everest, made his own trek up the Hill on Thursday, Nov. 7 to discuss his new book. Coburn revisited the first successful American expedition with slides, videos and insights into the physical, mental and geo-political obstacles that the group encountered 50 years ago.

Coburn’s opening bows and repeated articulation of “namaste” to the crowd gathered in Bradford Auditorium hinted at the cultural influences acquired via his work in Nepal for the Peace Corps, UNESCO, the World Bank and the World Wildlife Fund. Most significantly, Coburn’s post-Harvard venture to Nepal in 1973 inspired him to write a series of books on various Mount Everest expeditions.

In his introduction of the speaker, Publius Virgilius Rogers Professor of American History Maurice Isserman noted that he needed only to turn to his own bookshelf to find some of Coburn’s past works, two of which were on the New York Times bestseller list: Everest: Mountain Without Mercy and Touching My Father’s Soul: A Sherpa’s Journey to the Top of Everest. Coburn’s most recent book, The Vast Unknown: America’s First Ascent of Everest, highlights the journey of individuals, led by Swiss-Austrian Norman Dyhrenfurth, that propelled the nationalistic agenda of the Americans in a decade of political uncertainty. The book was published to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the first successful American ascent of Everest in May 1963.

Coburn began his lecture with a brief reminder of the context surrounding the launch of the 1963 expedition. Within the United States, the escalation of the civil rights movement created internal tension; globally, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the erection of the Berlin Wall, and finally the Soviet Union’s unveiling of Sputnik caused John F. Kennedy to make his famous and ambitious declaration of sending an American safely to the moon within the decade speech. This symbolic speech resonated with climbing enthusiasts: if we could get a man on the moon, how could we not get an American on the summit of Mt. Everest?

Ironically, it was a Swiss-Austrian who spearheaded the movement for an American expedition. After a failed climbing attempt in the Himalayas in 1952, where Norman Dyhrenfurth reached 27,000 feet before his expedition broke down, New Zealand’s Sir Edmund Hillary and Nepal’s Tenzing Norgay surpassed Dyhrenfurth and became the first climbers to conquer Everest. “This kind of tweaked Norman,” Coburn explained, and Dyhrenfurth made it his mission to create a team of unique individuals to give America a chance at claiming the summit. He filled the expedition with knowledgeable doctors, a psychologist, a sociologist, a National Geographic photographer, scientists and strong young men referred to as “SABs, or supremely abled bodies.”

The most integral members of the team joined the group once the Americans reached base camp in Nepal. Six months prior, a Sino-Indian war had broken out to the east and west of Mt. Everest. Unsure of the support that the Sherpas, the native people of the Himalayas, would give to a group of Americans straddling the line that separated a “geopolitically sensitive area,” the American group found solace in the willingness of the native Himalayans who agreed to aid the expedition effort. Just as the Sherpas were placing the climbers’ pajamas on top of sleeping bags in the tents each night, the American doctors on the expedition were holding evening medical clinics and providing children, porters and villagers with smallpox vaccine.

Tough moments along the grueling ascent of Everest required teamwork for the expedition to continue. When a 30-ton ice wall broke off of the mountain and crushed Jake Breitenbach while he climbed its surface, the expedition members had to fight their dejection and push through with the mantra that “they aren’t climbing without Jake, but for Jake.” Numerous other physical obstacles tested the group before Jim Whittaker and his Sherpa climbing partner Nawang Gombu planted the American flag on the summit of Everest. Not long after, two other members of the expedition, Barry Bishop and Lute Jerstad, reached the same summit by a more difficult West Ridge course while losing each of their toes to frostbite.

As a political instrument and cultural barrier breaker, the Everest expedition in 1963 exemplifies the qualities encouraged by John F. Kennedy in the politically tumultuous period. “It is my sincere hope that their legacy of teamwork, of collaboration, of persistence, and sometimes an elegant kind of compromise … will live on in future generations and especially in young people like you,” said Coburn, referencing the Everest climbers.

Posted November 10, 2013