What do slavery in 19th century England, foot binding in China, and dueling by the English elites all have in common? As Dr. Kwame Anthony Appiah explained, each of these practices was ended due to the mobilization of honor.

On Sept. 29, Appiah delivered the inaugural speech in this year’s Levitt speaker series, hosted by the Levitt Center, The Diversity and Social Justice Project, and the Philosophy Department. The goal of this series is to support the Hamilton College community’s dedication to social innovation by examining the numerous ways in which we can constructively address the social problems with novel solutions.

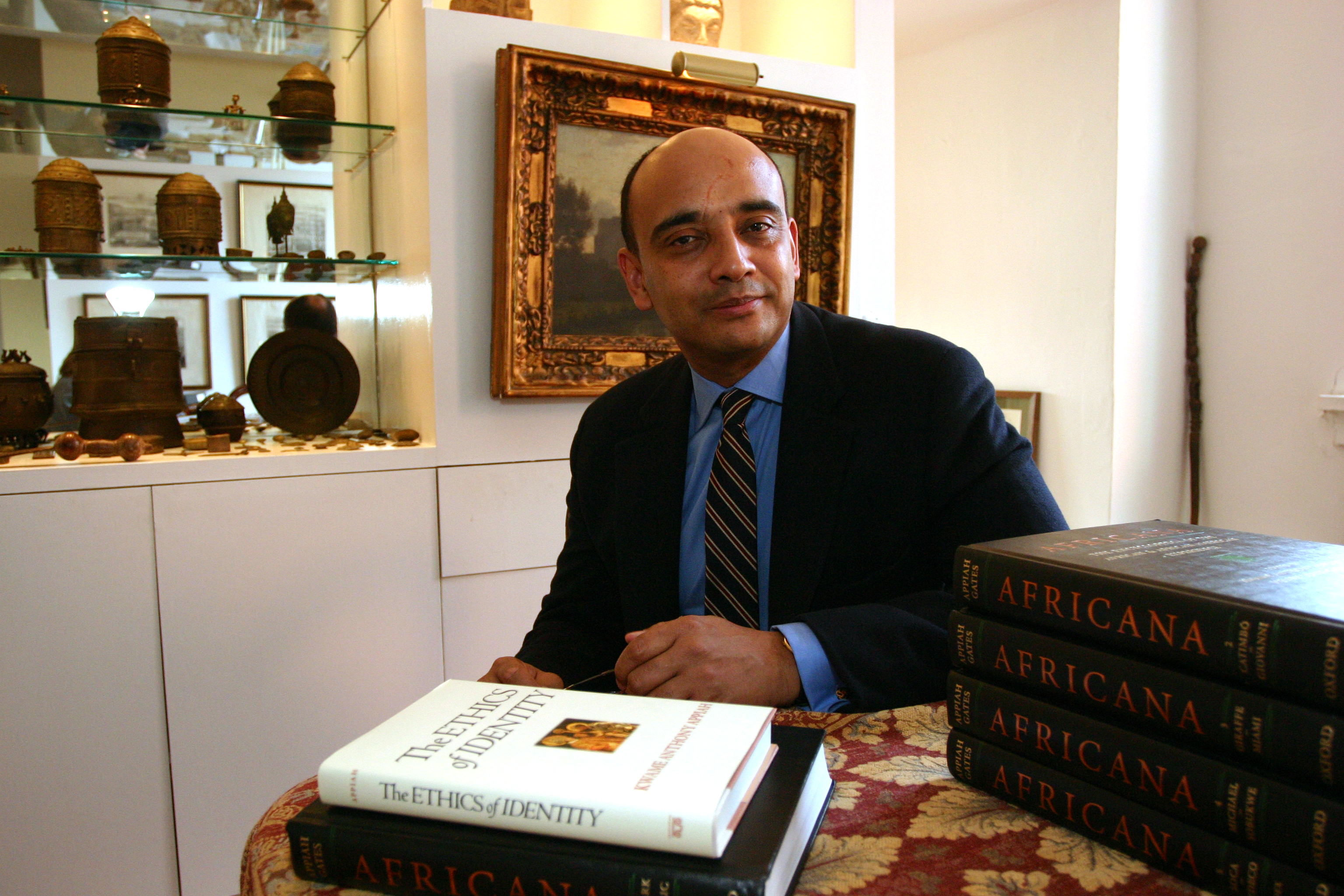

Appiah holds a bachelor’s degree and Ph.D from Cambridge University, and is currently a professor of law and philosophy at New York University, an accomplished novelist, and is touted as one of the foremost authorities on issues spanning from moral theory, to racial politics, to African intellectual history. His speech to the Hamilton community focused on how changing codes of honor can incite moral revolutions and social change.

He illustrated this theory through the examples of slavery and dueling in England, and foot binding in China. Though these practices contradicted logic, the law, and the church, moral and logical arguments were not enough to stop them. It was only when the honor code surrounding these three issues was altered that actual positive social change occurred.

When dueling expanded from exclusively a way for the British aristocracy to solve quarrels to a popular practice by the common man of England, the honor surrounding the tradition was changed. Now, for an English elite to participate in a duel was to bring great dishonor upon his name, as he would now be associated with the common men of Britain. Once this change occurred, there was a drastic and sudden drop in the prevalence of dueling.

Similarly, in China, though it was long known that foot binding was unhealthy, impractical and insensibly cruel, the practice was not eradicated until the country was able to see themselves through the eyes of the international community. It was then that they realized their national honor could only be repaired if they ended this barbarous custom. Again in England, slavery was not abolished on the grounds of its immortality, but instead when the British working class realized they could not take pride and honor in their work as long as labor was associated with inferiority.

In all three cases, social change was only set in motion when the honor code surrounding the issue changed itself. Appiah attributes this phenomenon to the power of honor and how much people care about how others regard them.

We can see this manifest itself negatively. For example, the practice of honor killing around the world, where males are allowed to murder a female family member if she has extramarital sex -- even if this sex is in the form of rape -- for the sake of protecting their honor. While it is true that honor can be mobilized to do harm, Appiah urged that we do not ignore honor as a means to do good as well. History has proven that if people can collectively come together to reshape the code by which we appraise honor to celebrate those who work to promote positive social change, and shame those who go against it, extreme and beneficial changes in the behavior of entire societies can occur.

Appiah began his lecture by noting that we live in an age of great moral advancements, but that we still have a long way to go. While honor is an extremely powerful tool in enacting positive social change, it cannot be controlled or utilized by individuals alone. Appiah stressed the importance that people understand the power of honor as a means to social change, so that they can have a better chance of collectively coming together to use it to enact the positive moral change we would all like to see.

Posted September 30, 2014