Janelle Rodriguez

April 30, 2025

We welcomed Zana Briski, the final artist to visit campus as part of Menagerie: Animals in Art from the Wellin Museum, a few weeks ago, and while the exhibition is open until early June, wrapping up the show’s visiting artist program feels bittersweet. Following on from highly successful visits by Craig Zammiello, and Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka, Zana provided another inimitable perspective on how creativity and the natural world can intertwine in an artist’s practice. Zana’s incredible Bearogram #10, New York (2020), a unique photogram created without the use of a camera, is the first artwork encountered by visitors to Menagerie, and has become a firm favorite. She chatted with the Wellin’s docents over coffee, answering questions about how she came the photogram process and co-creates her work with wild creatures.

Can you tell us how you came to make photograms of animals?

ZB: I'm obsessed with animals—I always have been. I wanted to be Dr Dolittle, although I wasn’t particularly exposed to animals as a child. I started as a documentary photographer, aiming for Magnum—hardcore. I was good at it, but after ten years of photographing in brothels in Calcutta—hard, heavy stuff—I said no more. During that project, I would wait until the doors closed at 11 o'clock at night and watch the rats and cockroaches, because I love any animals, and that was my only connection with nature. After that project I never photographed humans again. Somebody said to me, you can either sit at the gates of hell, or you can sit at the gates of heaven. I realized that I don't need to sit in suffering to change people's hearts and minds. I can look at beauty and what I love. That was a very profound realization.

From Calcutta, I flew to Rwanda to a friend who was heading up a mountain gorilla veterinary project. I started working with wildlife, using an unconventional panoramic camera, which meant that I needed to be very close. I spent two years testing different handmade Japanese papers to find signature materials that I could use to make beautiful prints. I was making these beautiful art objects to honor the animals that I was privileged to encounter.

After Rwanda, I worked with insects for fifteen years, inspired by the praying mantis. I went to Borneo, where I'd been going since I was nineteen years old, to primary forest, to photograph the insects. I would stay in the middle of the forest, and I would set up a light trap—a sheet with special lights, which attracts insects. My happy place is being alone in the middle of nature, the middle of nowhere, with any animal at all. I have a very special relationship with the night. It's magical, sacred and awesome to me, to be under the stars, to hear the sounds, to not know what's going on. I can really focus in a way that I can’t during the day. I would say it's just a level of expanded consciousness that I'm addicted to. My friend Chuck Kelton, who’s an incredible master printer, suggested that I take photo paper with me to Borneo. I told him that I didn’t like photograms, but I didn’t really know what a photogram was like. Chuck put a box of photo paper in my bag anyway, and I made some photograms of insects. The pictures were beautiful. I pretty much never worked with a camera after that.

How did you start working with bears?

ZB: I came to working with bears after renting a place in upstate New York, on the Hudson. There was a bald eagle nesting in a tree in the yard, and coyotes would run through, possums, raccoons, skunks—it was a wildlife corridor. I properly met my first skunk and named him Cream Puff because he was almost white. I met ten different skunks and I stayed up all night, every night, making skunkograms. At first, I put photo paper on the ground, which was interesting. Then I tried putting it vertically, but it was cutting off the feet, and so then I started curling the paper. It took five months of experimentation to figure out how to do it. I learned about how the vegetation looks on the paper, and what happens when it rains. I went back to Borneo to work with insects, and a Malayan civet who would come and eat the beetles at the bug sheet. So, I worked with them! That was my first trip overseas with mammals and photograms. I was completely hooked.

I went back to New York, upstate, and started working with the black bears. I had never met a bear, previously. One showed up one night—they're so impressive. I spent the next two and a half years with bears every night, when they were out. I bought every roll of photo paper that I could find. Ilford in England is pretty much the only company still making photo paper in rolls, and a lot of it's bad—fogged or old. If paper is fogged, it has been exposed to either heat or pressure. It can be banded, or gray. Sometimes it can be beautiful, but most of the time it's not good. Sometimes it takes months to get paper, so I always have to plan in advance. The biggest paper Ilford make is in 98-foot rolls. I would cut the paper at around 90 inches. I met probably twenty different bears over that period of time. I love them. I named them. They're all different and have their own personalities. I would just sit out, night after night, waiting for somebody to show up. Auggie is the smallest bear that I worked with—she was about a year and a half old.

How does your relationship with the bears work?

ZB: The bears know me. People ask if I sit in a hide, but what’s the point of that? I’d maybe work in a hide with animals that might be too scared to develop a relationship with me, but usually I’m just sitting there. I spend a lot of time walking, sitting, figuring out where animals are, what they're doing, what they're eating, where they're drinking, where they're swimming. I'm not habituating them, but they know me, so they're watching me. Bears are pretty easy to communicate with, and pretty sassy.

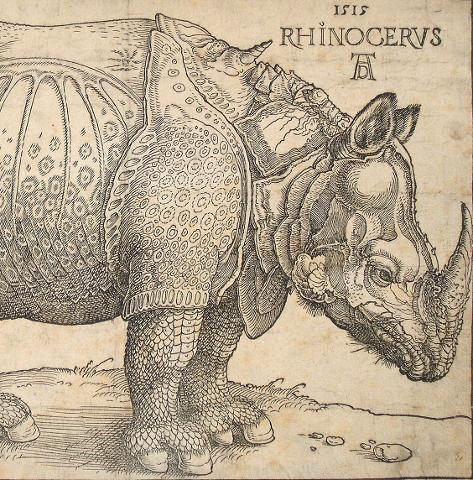

The number one question I get asked is, “aren't you scared?” I'm terrified of humans, but animals are great. I'm very aware, and very respectful. I'm not taking selfies with a rhino. I have no interest in being part of the picture. It's the animal’s choice— it is truly a collaboration, or co-creation. I just sit and wait. The worst part is falling asleep in the mud and waking up with ruined photo paper. The best is an incredible picture that I didn't even know happened until I get into the dark room, usually months later.

Is there an animal that you’d like to work with that you haven’t worked with yet?

ZB: I'm really obsessed with whoever I'm working with, and I’m heartbroken when I leave that place or that animal. But I have to say, I have wanted to make porcupineograms for ten years, with huge Cape porcupines, the ones in Africa. They're absolutely stunning—they would make such amazing pictures. I was just in Africa for four months, in different countries, and I had planned to work with the porcupines at the end of my trip, but I broke my leg and it didn’t work out. So, I have to go back. I love all the weird, black and white nocturnal critters that can take care of themselves—skunks, who can spray you, and porcupines, who have quills. But I've worked with everything, from praying mantises to whales. I'm always blown away by any animal.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.