Wednesday, February 26, 2025

We are lucky to have three artists visiting us as part of Menagerie: Animals in Art from the Wellin Museum. Following a great visit with Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka in the fall, we were excited to welcome Craig Zammiello—an artist, master printer, teacher, and amateur entomologist—before our final visiting artist, Zana Briski, arrives later in the spring. Craig’s print Hercules is currently on display in Menagerie (replacing Goliath), and he generously spent time visiting classes, engaging with students and faculty, and giving a public talk. Moreover, Wellin docents had a special opportunity to hang out with Craig and his favorite beetles, and pose him questions. We crashed their coffee hour to listen in (and snaffle some donuts).

When did you start collecting bugs?

CZ: There was a gentleman on Long Island who had a bug museum side-hustle set up in his house, selling things like little butterflies in frames. I was about ten years old, and I was fascinated. I bugged my parents, “Can I get a scorpion? Can I get a tarantula? Mom, please!” That’s how it started. I slowly kept at it until the late seventies. I also played in bands, and I happened to go over to another musician’s house. On the wall I saw these framed butterflies, from the same guy on Long Island. I thought “I’ve got to get more!” The guy on Long Island didn’t do it anymore, but my musician friend did. I wanted to do it too, and I slowly built up contacts all over the world. My collection grew and grew. About ten years ago I realized I couldn’t take care of this collection in my house anymore. I’d always thought that it would go somewhere, but never in my dreams did I think that it would go to the Museum of Natural History in New York City.

What’s your favorite bug?

CZ: I like beetles. I really like Goliath beetles—central African Cetonia flower beetles, so-called because they like to eat the pollen and sap from flowers. They’re scarab beetles, part of the Scarabaeidae. My collection went to the Museum of Natural History about four years ago, but I kept these Goliath beetles, and their cousins. Invertebrate-wise, my favorites are arachnids—large tarantula-type Theraphosidae spiders, and the giant centipede Scolopendra heros, which, if it was three feet tall, would rule the world. That’s my favorite.

Do you ever go to these places where the beetles are from?

CZ: Good Lord, are you out of your mind?! I’d be terrible out there. I have a phobia, and at the same time a fascination, of tropical areas. I’d love to, but I’d have to have a complete support staff, with doctors and a chef.

What made you want to incorporate your beetles into your artwork?

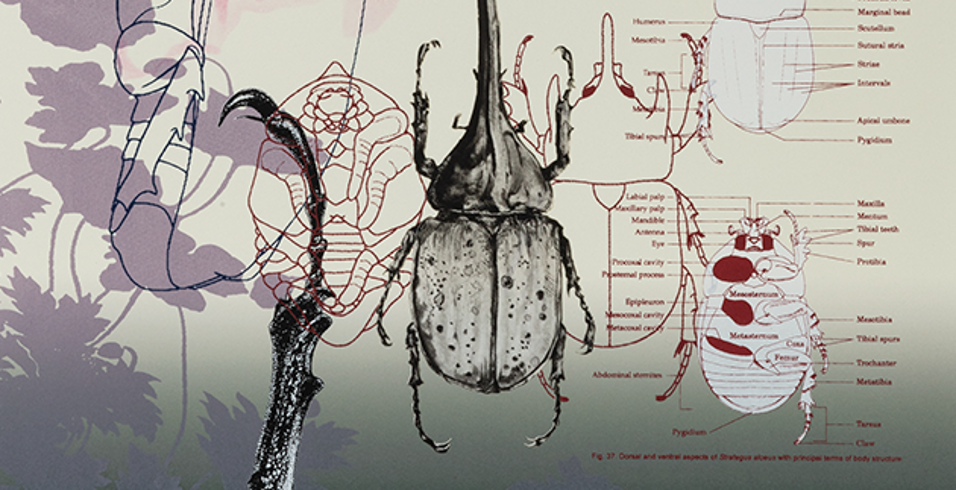

CZ: Before my collection went to the museum, somebody I work with at Columbia University said to me, “why don’t you make some prints before your bugs go away? Do some art with them.” I’d never done that before. I drew them, but only scientifically. It was a challenge, but I had a good time doing it. It was like paying respect to them as they leave. It was hard for me to do because I had to bridge artwork and scientific illustration, but it was fun to bring it together and employ different decorative elements. Color, for example. I don’t work with color for scientific illustrations.

How did you become a master printer? And can you tell us about that title?

CZ: Some people say it’s how many prints you’ve made, or how many techniques you know, or how long you’ve been doing it. It’s just a term. Sometimes someone will say “did you meet our master printer?” I’m always like, “where are they?” I’m looking for some elfin-looking older guy in a leather apron with clogs and a pipe. I’m a little more Nine Inch Nails. Also, from Long Island.

You mentioned that you teach, alongside making prints professionally. How did you get into teaching?

CZ: It’s a weird story. I’ve been teaching since I got out of high school. My school had a print studio and one of the art teachers was a printmaker, so in 10th grade I learned etching, lithography, and silkscreen—everything like that. After I graduated high school, I got into South Hampton College on Long Island. I went to register for classes, and the head of the art department came up and asked if I would like to teach our printmaking class as the teacher had quit. I was like, “Hi. I’m a freshman.” But I did it. I’ve been teaching ever since. In the late 1980s I started teaching at Long Island Art League, then at a state university, then New York University, and I’ve been at Columbia for around fifteen years now.

Has your experience as an educator influenced your artistic process?

CZ: Yes, definitely. I learn a lot from teaching. It’s the one thing that if I couldn’t do anything else, I would want to keep doing. I enjoy the interaction of teaching, and making prints is a part of that. I learn a lot from the students, and it helps keep me young.

Do you have a preferred printmaking process?

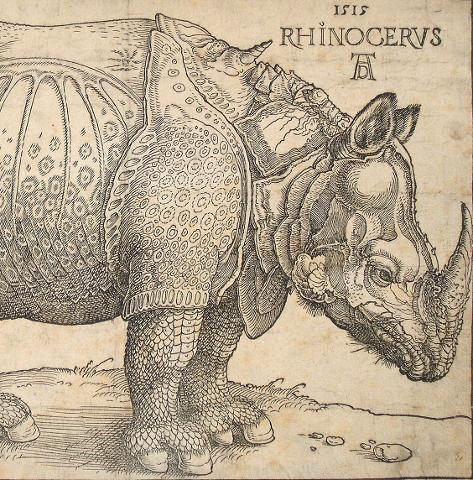

CZ: During the three years I spent printmaking in high school, I was drawn to figuring out how I could make something look like a photograph. It made me try to draw better. I was also interested in [Edward S.] Curtis’s The North American Indian series and how those had been made. By 1980, I was working at a print studio in Long Island where I was able to experiment with photogravure. Nineteenth-century photo-mechanical reproduction techniques are a passion of mine: photogravure, collotype, ambrotype, and Woodburytype—the holy grail of photo-mechanical reproduction. I think photogravure is fantastic, and I was able to use it later in my career, working with artists, in something called direct gravure, which is photogravure without a photograph.

Has printmaking changed a lot since you started out?

CZ: There are certain things that are fifteenth-century—you’re still carving a piece of wood—but when I left Universal Limited Art Editions in 2002 for Two Palms print studio it was like night and day—it wasn’t like typical printmaking. It was like, “what are you doing? God, you have a laser?!” Printmaking itself has changed, from the techniques to materials that aren’t made anymore. Even the idea of being safe—we used to wash our hands with kerosene in high school, but now I wouldn’t go anywhere in the print studio without a pair of latex gloves. What determines what’s called a print is a little loose now, which I have no problem with—I think it’s pretty cool. And the leather apron guys with the clogs aren’t around so much. In one way printmaking is always going to have a certain structure to it that is historical. But what’s the future of printing? To continue the processes of the future within that structure and keep evolving. Don’t be afraid to do something different. I encourage that.

Do you prefer working in collaboration or by yourself?

CZ: The word “collaboration” is so overused: I prefer the term “collusion.” The group effort in a print studio is like a drug. It’s addictive. When you produce something with a group of people, you’re on stage with them, in a way. You’re all rooting for something to happen. It’s really fun. And the next day, you do it again, with a different artist, in a different “language.” The artists who respond to this type of approach feel the same way. Jasper Johns would formulate his paintings based on his prints. Usually, it’s the opposite: you make a painting and say, “I think I’ll make a print of that and be democratic and sell it to different people and museums.” Jasper will work out an artwork through the mechanics of printmaking, with a group dynamic. That helps him structure it. Elizabeth Peyton comes in to work out paintings. She’ll make monotypes, where she paints with oil paint right onto plates and we print it. Don’t get me wrong, the print studio’s not for everybody. But in 48 years, there were only one or two artists that it didn’t work with, who didn’t respond. It also works in the opposite way. After five days of that, I’m glad to be home and doing my own drawing. Even if I’m drawing like Rauschenberg.

What’s been one of the biggest challenges of your career?

CZ: Jasper Johns hadn’t made an etching in twelve years and in 1986 he decided to make a group of etchings called The Seasons, based on a series of paintings that he’d made. In the Summer plate, one of the elements was a small polaroid of the Mona Lisa. I had a mentor at Universal Limited Art Editions who got the whole plate finished, and there was the little square on the plate where Jasper wanted a photogravure of the Mona Lisa. I was the photogravure person. If I messed it up, I messed up two months of work by Jasper Johns. I might as well jump off a bridge. Photogravure is a long process—it takes two days. And to put it into something that’s done—it had to work. I couldn’t start it again. I was lucky it worked. Everything’s been like cake after that!

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.