Alexander Jarman

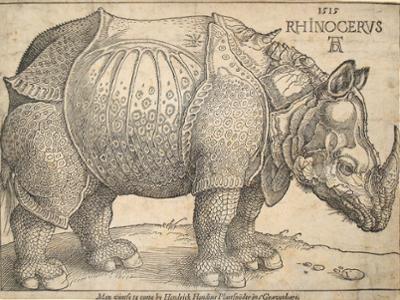

For the 2024-25 academic year, visitors to the Wellin Museum will find the exhibition gallery brimming with a diverse assemblage of objects, including ancient Roman coins, Mesoamerican ceramics, a Late Gothic altarpiece, photographs from the 19th through 21st centuries, and almost any medium and material one could imagine. One of the most intriguing, and deservedly popular, works in the current exhibition, Menagerie: Animals in Art from the Wellin Museum, is a modest-sized print tucked away in a drawer of an oak-paneled pedestal. When visitors open this drawer they will be confronted with a roughly 8.5 x 11 inch woodcut by Albrech Dürer, originally designed in 1515, (the Wellin’s copy was printed in the early seventeenth century) depicting a rhinoceros from the Indian subcontinent. The animal appears as if it is wearing a literal suit of armor and a rather peculiar horn emerges from between its shoulder blades. Several of the animal’s proportions are slightly askew but in many other ways, Dürer’s rendering rightly describes the visage of a modern, Indian rhinoceros (which has the wonderful scientific name of Rhinoceros unicornis.) And, of course, this is all the more incredible due to the fact that the artist never saw this rhinoceros, or any rhinoceros for that matter. In the exhibition’s accompanying video, Hamilton College art history professor Laura Tillery tells the story of the ill-fated rhinoceros, who never completed his journey from Portugal to Italy, and the textual description of the animal that Dürer relied upon to ultimately manufacture a depiction of this exotic creature that had not been seen in Europe for over a millennium.

Albrecht Dürer. The Rhinoceros, 1515. |

The story of “Dürer’s rhinoceros” is a fairly astonishing tale of translation. I highlight it for this blog entry because I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of translation—both literally and figuratively—as a result of many of the class visits we’ve facilitated this semester. To begin with, the Menagerie exhibition has proven useful to many of Hamilton’s language-based courses in a variety of ways. One such course I will highlight is HSPST-150, also known as Spanish Advanced Grammar and Composition. A major focus of this class is to “take Spanish out of the textbook and into real world usage,” exposing students to different uses of Spanish and thereby helping them learn to talk about an array of topics within a number of different contexts. Many of the artworks in Menagerie can transport viewers to a number of different cultures and time periods, and for students in HSPST-150, the discussion of Celia Vasquez Yui’s two sculptures Loro and Venado (both 2021) prompted a much longer conversation on some of the issues facing the Shipibo-Conibo people of modern-day Peru. This community faces a precarious economic future in large part due to increased deforestation on their lands, and Yui creates sculptures of animals now endangered due to this loss of habitat, using traditional Shipibo-Conibo craft techniques. The group discussion of these works by students in HSPST-150 during their gallery tour involved the use of words such as “extinción” (extinction), “parque de conservación” (wildlife preserve), deforestación (deforestation), and “contaminación” (pollution)—vocabulary that the professor stated would not otherwise have entered the class session. The fact that these terms revolved around Yui’s personal narrative as an indigenous artist-activist provided the students with a point of focus and context that was far more engaging than any list to be memorized from a textbook, and this is what makes in-gallery learning so special.

Celia Vasquez Yui. Vernado, 2021. |

One other, and more conceptual, example of the concept of “translation” being used at the Wellin this semester comes from a digital arts course called “Performance, Ritual, and Technology.” Students in this course were assigned a project requiring them to visit the museum in groups and choose an artwork that intrigued them for its narrative qualities. Just as Dürer relied on a written description of a rhino to make his woodcut of the animal, here each group of students wrote a description of their chosen artwork’s iconography and mood and fed that information into an AI-based image generator. The resulting visual images from the AI program served as the basis for the final component of the project—students had to write a new narrative in which the artwork and its AI-produced visual counterpart both came alive and confronted each other for a heated conversation regarding issues of authenticity, originality, and translation. These stories were then performed in the gallery, with the AI images projected on the walls next to the artworks and students narrating the dialogue. The resulting performances were engaging, entertaining, and thought-provoking. Where does authorship and ownership begin and end? When do reproductions become something unique? How does written language relate to visual images and when is translation more akin to interpretation? This blog won’t try to answer any of these questions, but rather just reinforce the unique possibilities that analyzing works of art can offer to students, faculty, and visitors. Art has a way of reminding us how little in our universe is fixed or certain. Our understanding of the world is always a process of translation and interpretation.