Images courtesy of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College.

Hidden within the file cabinets on the second floor of the Wellin Museum are hundreds of artworks, including lithographs, photographs, worn sketchbooks, and even small artifacts from ancient civilizations. These works are stored in very particular ways, ensuring that objects such as fragile newspaper clippings from the 19th century avoid contact with works done on Masonite board, which tend to deteriorate even when stored properly. By housing each individual piece carefully, the Wellin ensures that they are conserved and remain undamaged. Along with other students, I’m responsible for cataloguing these works into our online database, giving me the opportunity to explore each piece visually and historically.

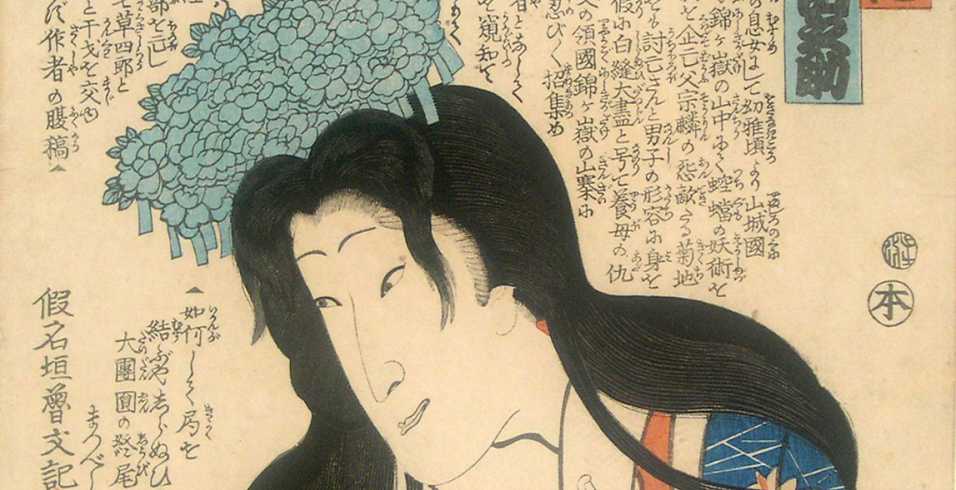

I was recently assigned to catalogue a group of Japanese woodblock prints. Several of these were from the Edo period, depicting portraits of actors, respectable family members, and even reclined lovers. While they are not dominant in size, they are vivid in color and pattern, demonstrating how each artist focused on how these designs affected the portrayal of the subject. Backgrounds also played a role in some, but were deemphasized through the use of lighter gradients and thinner outlines. However, each print had something in common: the integration of Japanese kanji, a system of writing utilizing Chinese characters.

Since I’m currently studying Japanese and plan to study art in Japan next spring, I’m extremely interested in how these artists incorporated the written word into their art. Words can be used to identify a character, convey an idea, or even tell an entire story, thereby adding an extra dimension to the piece. One of the prints in particular, Sawamura Tanosuke as Lady Suzuhiro Casting a spell of revenge, was dominated by kanji in the background. It’s likely that it tells a mythical story that gives more context regarding the subject’s motivations and actions. However, I’ve only learned basic kanji, such as “teacher,” “family,” and “mountain,” so I can confidently say that I’m too early in my studies to read a majority of the ones included on this print.

This language barrier is further increased because the number of kanji used today is significantly less than the number used in the Edo period. Despite this, I attempted to translate some of the simpler characters. I used a Japanese phone app that makes it easier to search for kanji based on the number and type of strokes, but it proved to be a lot trickier than I thought. By the end of this swift exploration, I was only able to translate one kanji as “heaven,” which was incredibly satisfying as a growing student.

This experience was only a small introduction to the vast world of Japanese prints, and while it was virtually impossible to read them, it has motivated me to further explore prints and discover how Japanese culture and text inspired these artists.