For slightly more than a century, the Hamilton honor code has provided an important moral compass for the student body. Incoming students have agreed to “abstain from dishonesty in all academic work” and “to take action and to report violations of the honor code to the proper authorities.” Despite its communal significance, the document that most recent classes of incoming students have signed has been a prosaic, mass-produced form printed on yellow copy paper.

Under the leadership of Visiting Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing Andrew Rippeon, the students in the Letterpress Printing and Book Arts Experience Adventure orientation group created a new honor code document that – from both tactile and visual perspectives – conveys the seriousness of its message. In the process, the students have learned “a ton about letterpress printing,” according to Jerad McMickle ’19, one of the group participants. “We all went into it blind. I [soon] realized that letterpress printing was a laborious, demanding and long process. In the digital age it's easy to think of printing as a process that lives and dies by Microsoft Word's ‘print document’ button, but the physical process requires multiple steps that each had large margins of error.

“The most unexpected aspect of the printing process, for me, was how easy the physical ‘printing’ part was. I always imagined that the set-up for letterpress printing a document would be simple, and that the difficult part would be printing it, but the opposite is true. It turns out that type-setting (arranging multiple lead ‘sorts,’ or letters) was by far the longest process, and setting the 14 lines of the Hamilton College honor code took upwards of four hours to complete. In comparison, we managed to print out the entire edition (550 copies) of the honor code in around the same time,” McMickle explained.

During their five days together, the group visited several regional letterpress studios and facilities in Central New York, including the Press and Letter Foundry of Michael and Winifred Bixler, the Wells College Book Arts Center in Aurora and Boxcar Press in Syracuse. Following the group’s introduction to the college's Rare Books/Book Arts collection, the group traveled to Boxcar Press to produce a press-ready plate of the College seal.

For the next two days, the 10 students and two students leaders along with Rippeon worked at the Bixlers' renowned letter foundry and book-bindery where they chose the color and layout, handset the lead type, cast (in hot metal) and set the text of the code and printed an edition of 550 copies of the honor code. “Because of the nature of letterpress, our two-color design meant that we had to print the cards twice, one full print run for the blue seal and another full print run for the black text, for a total of approximately 1,200 passes through the press,” Rippeon explained.

“The students designed, handset and proofed everything, and other than a few set-up prints that I and the Bixlers, the owners of the foundry, printed, the students in fact printed all of these prints. At the end, they were quite tired, but also (I think) very proud!” Rippeon concluded.

One student, Juan Hernandez ’19, expressed the focus, energy and resulting satisfaction involved in producing an error-free document. “I liked having an involvement with the honor code, as I felt a sense of responsibility for getting it right, as well as a drive for making my mark upon it. For example, I was able to spot two critical, yet hard-to-find errors, including the letter ‘s’ being upside down on the word ‘signature,’ and the word ‘honor’ having a ‘zero’ instead of an ‘o.’ Because of the nature of traditional analog letterpress printing, the letters, words and spacing had to be hand set individually, allowing for mistakes to occur easily. Personally, being able to closely see those subtle errors before the final documents were printed was important to me, and gave me much satisfaction with what I did.”

On Saturday, the group arrived at Wells College to view important historical material related to typography and design at the Book Arts Center. The students were able to work collaboratively, designing and printing an eight-panel accordion-fold booklet in five colors in an edition of 40. “After that day, they said they appreciated the labor that went into making the code, and the freedom that they later had designing their own booklet at Wells,” said Rippeon.

In summarizing his experience, McMickle said, “The most enjoyable aspect [of the trip] was the strong sense of bonding paralleled with the progression that comes with making a physical product. More so than most other trips, our XA trip had a clear end goal that required strong teamwork and communication to accomplish. It was very enriching and exciting to see my friendships with my peers grow as we ran roughly 1100 prints of the Honor Code.”

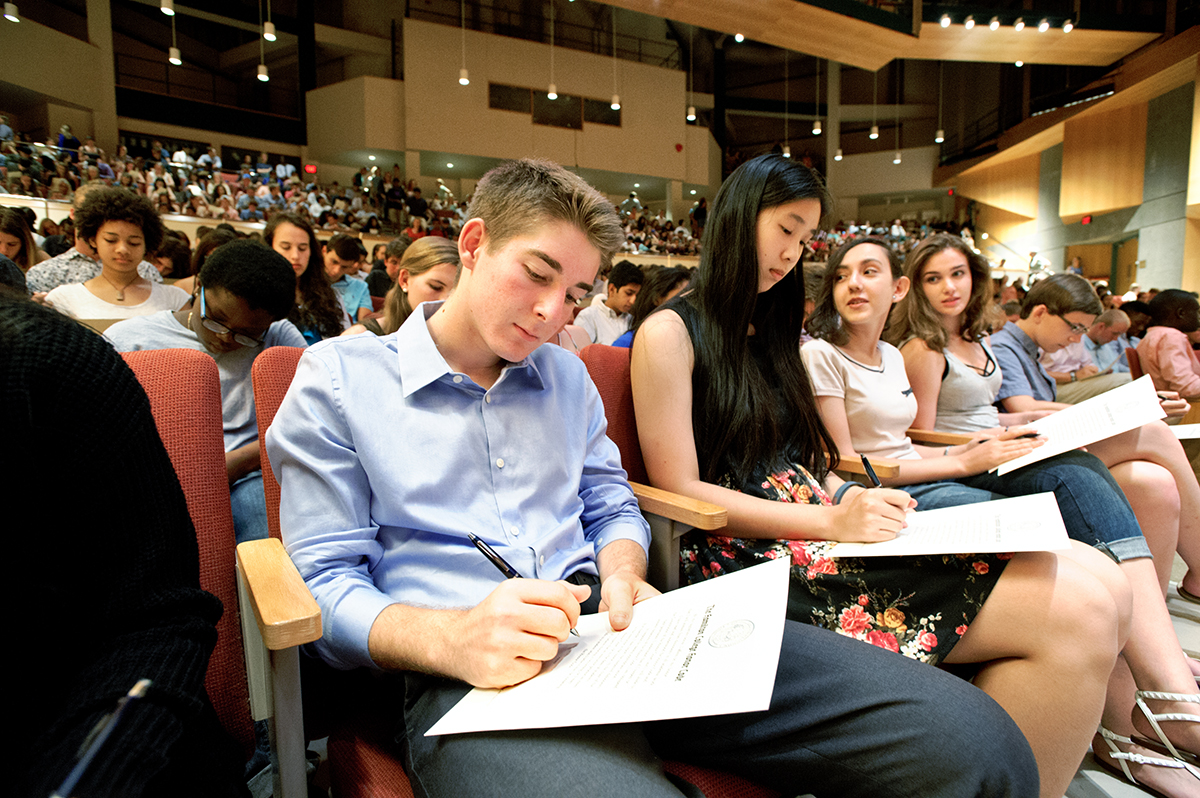

The group delivered their work to Associate Dean of Students Steve Orvis, who declared it “Fabulous! ... Exactly what we hoped for.” In a shift in tradition, the documents were distributed during convocation along with honor code pens, a gift and code reminder from the Dean of Students office. After first-year students signed their copies, orientation leaders collected them and Honor Court Chair Taylor Elicegui ’17 presented them with Conor O’Shea ’18, a member of the court, to President Stewart.

Letterpress Printing on Campus

This project was by no means Rippeon’s first foray into letterpress printing. For more than two years, he has been working, first restoring, then managing the move of and ultimately using a college printing press that had been abandoned many years ago. With a decade of experience working on a press in Buffalo and doing literary prints such as event posters, poetry broadsides and chapbooks, he was able to engage in a number of projects at Hamilton. These have included broadsides for the English department's visiting writers, a keepsake for the Milton Marathon Reading, a large-format broadsheet for the International Writers Festival and a project with the literary magazine Red Weather, among others. For the majority of these projects, students have been involved in setting type, making design decisions and actually operating the press.

The majority of the equipment – presses and ancillary equipment made of lead and wood – that Rippeon and the students under his direction use is no longer being made. This means that "new" equipment is located in one of two ways: donation or purchase on the used market which is unpredictable and expensive. Rippeon continues his search for equipment, types, or even printing stock, as he develops the college’s resources in this area.